Tutorial: Counterpoint in tenths - contrapunto de dezenas

Three- and four-part improvisation with tenths in the outern voices.

Historical Introduction

When several counterpoint singers improvise simultaneously to a chorale, the question of coordination between the voices arises. Because even if everyone improvises to the chorale according to the rules, unwanted dissonances or parallels can arise between the improvising singers.

Throughout the history of music, various techniques and strategies have been developed to deal with the issue of coordination. One solution, which was popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, is the contrapunto de dezenas, in which the upper voice sings consistently in tenths to the chorale (in the bass). The middle voice can thus avoid problems with the upper voice and at the same time has room for manoeuvre.

Contrapunto de dezenas is more demanding than some popular improvisation techniques, which were also practised by amateurs. Nevertheless, compared to the ambitious Contrapunto concertado (see tutorial on this), it was a kind of ‘makeshift solution’. In the words of Pedro Cerone:

‘Notice that sometimes, for lack of singers who can counterpoint, people tend to do the following three-part counterpoint: The soprano always sings in tenths to the chorale, [...]. And even if some people don't quite like this kind of counterpoint because of all the tenths, you can still do it this way in an emergency if you can't do any better. Because sometimes, in times of need, the rye or millet bread you have is much better and tastier than the wheat bread you can't have.’ Cerone 1613, p. 593

Sources that describe the contrapunto de dezenas or provide helpful information on it are:

- Vicente Lusitano: Arte de Contrapunto, c.1550, (Paris, Bibliothèque national de France, Espagnol 219; edition: Philippe Canguilhem 2013)

- Vicente Lusitano: Introduttione facilissima, et novissima, di canto fermo, figurato, contraponto semplice, et in concerto, Roma 1553

- Pedro Cerone: El Melopeo y Maestro, Napoli 1613

- Pablo Nassarre: Escuela Musica, Segunda Parte, Madrid 1723

A brief reference should be made here to earlier varieties of contrapunto de dezenas that can be found in Guilielmus Monachus' De praeceptis artis musicae (c.1480). One type is a quasi fauxbourdon with transposed upper voices (continuous fifth parallels!). In the other, the outer voices are improvised in coordinated tenths from a given middle voice. These types are not the subject of this tutorial.

Three-part framework

The Contrapunto de dezenas is usually practised with a plain chant in the bass, although this can also be improvised over a mensural melody (see last section of this tutorial). In principle, it would also be possible to take a given melody in the upper voice and improvise underneath it.

In the following we explain the standard case with the plain chant in the bass in long bars (alla breve). Even though the upper and middle voices can be improvised at the same time, for methodical reasons we will deal with the upper voice first and then the middle voice.

Upper voice

The upper voice can either simply form tenths to the bass (Puntos llanos), or diminish the tenths framework.

Puntos llanos

Cerone describes the Contrapunto de dezenas in such a way that the upper voice is limited to tenths, while the middle voice is diminished.

‘The soprano always sings in tenths to the chorale by imagining the key of the canto llano, but one line lower; so that every simple note (punto llano) is a tenth to the plain chant. Then the third, which makes the diminished counterpoint in the middle voice [...]’ (Cerone 1613, p. 593)

Note how Cerone gives a reading trick for the upper voice: If you imagine the clef of the plain chant a line lower, you automatically sing a third higher. However, as the upper part is sung by boys (or women), it sounds an octave higher, i.e. a tenth above the plain chant.

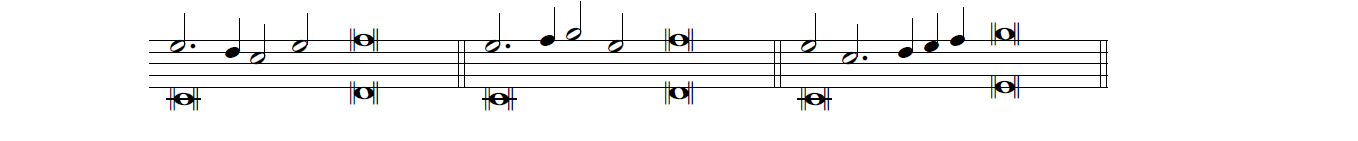

In this video you can see how this principle is applied to the Christmas Alleluia dies sanctificatus. If the upper voice imagines the F clef on the second line (instead of the third), then its first note is an E. (1)

Diminution

While Cerone suggests an undiminished upper voice, Lusitano shows us a diminished upper voice in his examples (c. 1550 and 1553). In this video we can hear the Alleluia dies sanctificatus again, but with such a diminished upper voice.

To ensure a good progression of the upper voice, it is advisable to follow Ortiz's recommendation:

‘The most perfect way [to diminute] is to return to the main note [...] after the glossa (diminution) before proceeding to the next main note.’ (Ortiz, Trattado de Glossas, Napoli 1553, preface)

Thus, where the plain chant moves from one note to the next, the interval progression in tenths is maintained.

One way of shaping the melody is to go to the octave or twelfth in the middle of the bar and then return to the tenth in the last minim of the bar.

While the octave works without any problems, you have to make sure that the middle voice does not go to the sixth at the same time with the twelfth, otherwise there will be an unexpected dissonance between the two counterpoint players.

Another possibility is the use of the eleventh as a fourth suspension, if the conditions are right - we will deal with this later in the cadences.

We recommend the following exercises for training the upper voice (with or without diminution):

middle voice

open rules

Cerone explains the improvisation of the middle voice as follows:

Then let the third who makes the diminished counterpoint in the middle voice observe that he never makes two imperfect consonances of the same kind in succession without another consonance between them, whether perfect or imperfect. For if he makes two thirds with the lower voice, he will make two octaves with the upper voice; and if he makes two, three or more sixths with the lower voice, he will make as many fifths with the upper voice. (Cerone 1613, p. 593)

In other words: the middle voice can take all consonances (3, 5, 6 and 8), but cannot move any of them parallel to the bass - not even the imperfect consonances, which form forbidden parallels to the upper voice (thirds to the bass result in octaves to the upper voice, sixths to the bass result in fifths).

Parallel movements with different intervals are also problematic, as they result in hidden parallels (to the bass or the upper voice). This means that the middle voice should always progress in contrary or lateral motion.

systematic use of 8 and 5

In principle, the middle voice has a choice between four possible consonances (taking into account the prohibition of parallels). Experience has shown, however, that it is not easy to cope with this ‘agony of choice’ at the beginning. It has proved helpful to have a certain standard solution.

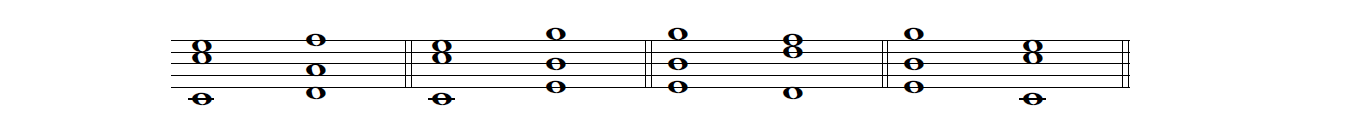

One such standard solution can be found in Nassarre, who explains the basic rules for voice leading in three-part harmony. He differentiates according to whether the bass makes smaller movements (seconds, thirds) or larger leaps (fourths, fifths). For the smaller progressions he writes:

‘If the plain chant moves up a second or a third, the usual disposition is that the octave goes to the fifth and the tenth to the tenth. [...] If the plain chant moves down a second or a third, then the fifth goes to the octave and the tenth to the tenth.’ (Nassarre 1723, p. 232)

For second and third progressions of the plain chant (which are the more common ones anyway), one voice always moves in tenths. The other voice combines fifths and octaves depending on the direction of movement of the plain chant:

- with ascending plain chant, the middle voice moves downwards from the octave to the fifth

- with descending plain chant, the middle voice moves upwards from the fifth to the octave

If the Canto llano constantly changes direction (quasi zig-zag-like), the arrival interval at the new note is automatically the starting point for the next progression. You can practise this with the following exercise:

If the Canto llano goes up several times in succession, the middle voice must always change to the octave in the middle of the bar in order to move back down the fifth (= counter-movement) at the beginning of the next bar. The same applies downwards: you change to the fifth during the bar in order to reach the next octave upwards.

It is advisable to practise such progressions over the hexachord.

You can then practise this principle with ‘real’ cantos llanos, so that the various progression possibilities are mixed together:

Footnotes

(1) You can hear in this example how the upper voice sings musica ficta (accidentals) by singing B instead of B over the 4th, 5th and 7th notes of the canto llano (G). As she progresses from A (here solmised as la) a single step upwards and then downwards, the solmisation rule applies here, which says "una nota supra la semper est canenda fa ’, which leads to a semitone progression. The 11th note is also a G, but progresses further upwards. The upper voice must therefore change to a different hexachord and sing a B (mi).

Another case where musica ficta may be required is the final cadence: the last note (ultima) must be a major tenth, as the minor tenth is not considered ‘perfect’ (conclusive) enough. If a minor tenth results from the diatonic scale, then it should be augmented accidentally (‘Picardy third’). In the ultima of an internal cadence, the application of this principle is not obligatory, but possible.